A family’s regular beach clean-up in Western Australia led to a discovery that reached across more than a century. On 9 October, the Brown family found a glass bottle washed up on Wharton Beach near Esperance, containing handwritten letters from two Australian soldiers who were en route to the Western Front during the First World War. The letters, dated 15 August 1916, were written by Privates Malcolm Neville and William Harley aboard the troopship HMAT A70 Ballarat . What began as a simple day of picking up rubbish turned into a moving encounter with the voices of men heading to war.

A bottle from the past

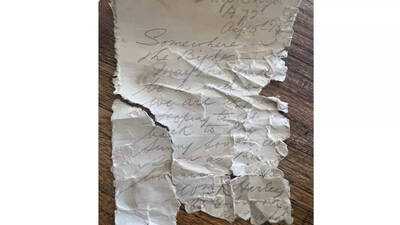

The bottle, an old Schweppes-branded glass bottle, was spotted just above the waterline by Peter Brown and his daughter Felicity while riding quad bikes along the beach. Thinking it was litter, they picked it up as part of their regular clean-up. But instead of rubbish, the Browns found two neatly folded pieces of paper written in pencil, remarkably legible despite being damp.

Deb Brown, who later opened the bottle, described the moment as surreal. “We do a lot of cleaning up on our beaches and would never go past a piece of rubbish. So this little bottle was lying there waiting to be picked up,” she said. The letters were dated 1916, written when the soldiers were somewhere in the Great Australian Bight, bound for Europe.

The message of the soldiers

Privates Malcolm Neville, aged 27, and William Harley, aged 37, were travelling aboard the Ballarat, which had departed from Adelaide on 12 August 1916. They were part of a reinforcement unit for the 48th Australian Infantry Battalion, destined for the battlefields of France.

Neville’s letter was addressed to his mother, Robertina Neville, in Wilkawatt, South Australia, a small settlement now almost deserted. He asked that whoever found the bottle deliver the note to her. In contrast, Harley, whose mother had died, wrote that the finder could keep his message as a memento, wishing them good health.

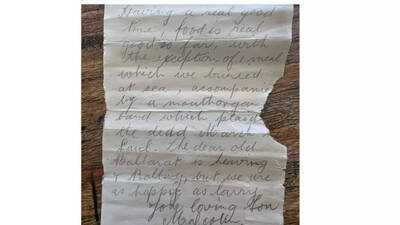

Both letters carried a mix of optimism and humour that belied the grim future awaiting them. Neville described life on board:

“Having a real good time, food is real good so far, with the exception of one meal, which we buried at sea.”

He signed off “Somewhere at Sea”, writing that the ship was “heaving and rolling, but we are as happy as Larry”.

Harley wrote that they were “Somewhere in the Bight” and ended his note with the cheerful line:

“May the finder be as well as we are at present.”

The letters reflected the light-hearted spirit of young men embarking on a perilous journey, perhaps unaware of the horrors that lay ahead.

Fates divided by war

The two soldiers’ lives took starkly different turns after their hopeful words were sealed in the bottle. Private Malcolm Neville was killed in action a year later on the Western Front. Private William Harley survived the war but was twice wounded and later died in 1934 from cancer that his family believes was caused by German gas attacks in the trenches.

More than a century later, their stories resurfaced, connecting descendants who never expected such a find. “It really does feel like a miracle,” said Ann Turner, Harley’s granddaughter. “It feels like our grandfather has reached out for us from the grave.”

How the bottle survived

Experts believe the bottle did not travel far. Deb Brown suspects it was buried in sand dunes for most of the past century before being unearthed by recent coastal erosion. “It’s in pristine condition,” she said. “If it had been at sea all this time, the paper would have disintegrated. The dunes must have protected it.”

The writing, though faded, remained clear enough to read. The Browns contacted both soldiers’ families to share the discovery, bringing together relatives who were deeply moved by the connection.

For descendants of the two men, the discovery has become a bridge between generations separated by war and time. Herbie Neville, great-nephew of Malcolm Neville, said his family was “brought together” by the find. “It sounds as though he was pretty happy to go to the war. It’s so sad that he lost his life. What a man he was,” he said.

A bottle from the past

The bottle, an old Schweppes-branded glass bottle, was spotted just above the waterline by Peter Brown and his daughter Felicity while riding quad bikes along the beach. Thinking it was litter, they picked it up as part of their regular clean-up. But instead of rubbish, the Browns found two neatly folded pieces of paper written in pencil, remarkably legible despite being damp.

Deb Brown, who later opened the bottle, described the moment as surreal. “We do a lot of cleaning up on our beaches and would never go past a piece of rubbish. So this little bottle was lying there waiting to be picked up,” she said. The letters were dated 1916, written when the soldiers were somewhere in the Great Australian Bight, bound for Europe.

The message of the soldiers

Privates Malcolm Neville, aged 27, and William Harley, aged 37, were travelling aboard the Ballarat, which had departed from Adelaide on 12 August 1916. They were part of a reinforcement unit for the 48th Australian Infantry Battalion, destined for the battlefields of France.

Neville’s letter was addressed to his mother, Robertina Neville, in Wilkawatt, South Australia, a small settlement now almost deserted. He asked that whoever found the bottle deliver the note to her. In contrast, Harley, whose mother had died, wrote that the finder could keep his message as a memento, wishing them good health.

Both letters carried a mix of optimism and humour that belied the grim future awaiting them. Neville described life on board:

“Having a real good time, food is real good so far, with the exception of one meal, which we buried at sea.”

He signed off “Somewhere at Sea”, writing that the ship was “heaving and rolling, but we are as happy as Larry”.

Harley wrote that they were “Somewhere in the Bight” and ended his note with the cheerful line:

“May the finder be as well as we are at present.”

The letters reflected the light-hearted spirit of young men embarking on a perilous journey, perhaps unaware of the horrors that lay ahead.

Fates divided by war

The two soldiers’ lives took starkly different turns after their hopeful words were sealed in the bottle. Private Malcolm Neville was killed in action a year later on the Western Front. Private William Harley survived the war but was twice wounded and later died in 1934 from cancer that his family believes was caused by German gas attacks in the trenches.

More than a century later, their stories resurfaced, connecting descendants who never expected such a find. “It really does feel like a miracle,” said Ann Turner, Harley’s granddaughter. “It feels like our grandfather has reached out for us from the grave.”

How the bottle survived

Experts believe the bottle did not travel far. Deb Brown suspects it was buried in sand dunes for most of the past century before being unearthed by recent coastal erosion. “It’s in pristine condition,” she said. “If it had been at sea all this time, the paper would have disintegrated. The dunes must have protected it.”

The writing, though faded, remained clear enough to read. The Browns contacted both soldiers’ families to share the discovery, bringing together relatives who were deeply moved by the connection.

For descendants of the two men, the discovery has become a bridge between generations separated by war and time. Herbie Neville, great-nephew of Malcolm Neville, said his family was “brought together” by the find. “It sounds as though he was pretty happy to go to the war. It’s so sad that he lost his life. What a man he was,” he said.

You may also like

'Bodies kept coming': 132 killed in Brazil's deadliest police operation against drug gangs; how it unfolded

Bahraich Boat Tragedy: 24 Missing After Boat Capsizes in Kaudiyala River, CM Yogi Orders Urgent Rescue Operation

Vastu Secrets for Prosperity: Keep These 5 Auspicious Items in the North-East Corner to Invite Goddess Lakshmi's Blessings

Dev Uthani Ekadashi 2025 Date: Is Prabodhini Ekadashi on 1st or 2nd November? Check exact puja timings, tithi, parana and significance

Sonya Massey called the cops for help. They shot her dead in her own home